The Songs

of Elizabeth Cronin

The Songs of Elizabeth Cronin, Irish Traditional Singer: The Complete Song Collection. Dáibhí Ó Cróinín, editor. Four Courts Press, Dublin. 2000. ISBN 1- 85182-259-3. 332 pp. Book plus 2 Compact Discs

The next singer, on the other hand, conjures up with her style of singing the image of a restless moorland stream, always in motion, running, gliding, falling in short cascades, swirling, eddying and moving to the sea. She is Mrs Elizabeth Cronin, a seventy one year old woman with a true blas, that is the true singing style of County Cork. She uses mordents, often two or more joined together, passing notes flowered like ornaments, sighing notes and sudden stops and all of them combine in a joyful vision of endless motion.

Ewan MacColl[1]

Of all the performers recorded in that outburst of collecting which followed the wake of the Second World War, few deserved or achieved higher acclaim than Elizabeth Cronin. Whether you look for skilful execution, for choice of repertoire, or simple honest communication of human feeling, Elizabeth Cronin set the standard by which others were judged. Up to now though, she has been singularly ill-served on record and in print. Nobody has produced a biography of her, as Roger Abrahams did with Almeda Riddle, or James Porter and Herschel Gower did with Jeannie Robertson. For that matter, I cannot recall a single magazine or journal article devoted to her. Her appearances on record have been limited to a small number of anthologies, and to one or two of Peter Kennedy’s Folktracks cassettes, with all that the latter implies in terms of poor packaging and sound quality.[2] Yet her influence on modern singers is such that key constituents of her repertoire have permeated practically the entire present day Irish traditional singing world. Without Elizabeth Cronin, subsequent generations would not have known Lord Gregory, or The Green Linnet, or The Bonny Blue-Eyed Lassie, or her version of Siúil A Rúin.

Small

wonder then that, when Four Courts Press announced this double whammy of a book

plus two CDs, they clearly thought they had a major contribution to the study

of folk music on their hands. Unfortunately, to play in the big league you need

more than scintillating subject matter. You need impeccable editorial

standards, meticulous scholarship and accuracy of the highest

degree. Well, the book certainly looks as though it has been thoroughly

edited and researched, and there are copious notes and references. Close

inspection, however, reveals a different story.

Small

wonder then that, when Four Courts Press announced this double whammy of a book

plus two CDs, they clearly thought they had a major contribution to the study

of folk music on their hands. Unfortunately, to play in the big league you need

more than scintillating subject matter. You need impeccable editorial

standards, meticulous scholarship and accuracy of the highest

degree. Well, the book certainly looks as though it has been thoroughly

edited and researched, and there are copious notes and references. Close

inspection, however, reveals a different story.

I’ll thicken the plot of that one shortly. First though, I need to unload a bone of contention; namely that I feel the audio side of this production should have been given much greater prominence. The complete package consists of an A4 size book, which itemises every song known to have existed in Mrs Cronin’s repertoire, plus a pair of compact discs in plastic wallets mounted on the inside back cover. The discs, which contain a very generous selection of examples of her singing, are announced in a triangle measuring slightly more than two square inches in the top right hand corner of the book’s front cover. Also, a superscript number alongside relevant song titles in the text tells you which track and which disc that song can be found on. Otherwise, unless I’ve missed something, there are only two other references to the CDs in the entire book. They consist of an appendix on page 310, which takes the form of a note from Nicholas Carolan, who produced the discs, and a track listing on the very last two pages. I am surely not the only one who feels that the cart has been put before the horse, and that this should have been a double CD of Mrs Cronin, plus supporting book. Nevertheless, a book with two CDs is what landed on my desk. A book with two CDs is what I shall review.

The hard copy part, then, comes complete with all the usual mod cons. The habitual introduction is followed by a set of song texts, with musical notations for those songs where Mrs Cronin’s melody is known, plus a significant number of titles for which no texts or melodies were ever recovered. In total, one hundred and ninety six repertoire elements are accommodated. There are some vivid photographs, several appendices, a large bibliography, and a surprisingly short discography which lists only the commercial recordings. There is the usual preface with the usual acknowledgements. This latter is substantial and indicates that Mr Ó Cróinín has got round a fair number of people. Luminaries as diverse as Peter Kennedy, Donal Lunny, and Nicholas Carolan are credited, as is a member of the Department of Microbiology at the Galway campus of the National University of Ireland. There is also acknowledgement of one Dr Alan Seeger, who is identified as curator of the Folkways collection at the Smithsonian Institute. There is no Alan Seeger at the Smithsonian. At the time this book was published, the Folkways collection was in the capable hands of Dr Anthony Seeger. A small mistake, perhaps, but the first of many.[3]

Allow me to begin by showing you round the introduction. It is titled Bess Cronin 1879 -1956[4] and broken into sections which are respectively headed: The Early Years; Baile Mhúirne at the Turn of the Century; The Early Collectors in Baile Mhúirne; The Collectors From Bess Cronin; How Bess Learned Her Songs; and The Commercial Recordings. From the main title, and those of various sections, I would have expected a rigorous account of the life and times of Bess Cronin. We don’t get one. What we get in that opening section is a thumbnail sketch of the first couple of decades of Mrs Cronin’s life. It details her birth date, the names and birth years of some immediate family members, her father’s occupation, the fact that she was boarded out to her uncle’s farm in her mid-teens, and that her formative years were the period when she acquired most of her songs. That is virtually the whole nutshell. However, it would have been a miracle if Dáibhí Ó Cróinín had crammed any more in, for the entire section is only eight lines long!

From there, we are launched into a discourse on Elizabeth Cronin’s home village at the turn of the century - he does of course mean the twentieth century. For those less than familiar with the lady, Elizabeth Cronin was born in Baile Mhúirne in west Cork - near the town of sweet Macroom, as the song says - and spent her entire life in that neighbourhood. Dáibhí Ó Cróinín is her grandson. This second section does not mention Elizabeth Cronin at all. Neither is it a piece of ethnological data, which could have set the Baile Mhúirne song tradition in a useful social context. Instead, it describes the activities of certain members of the local intelligentsia, and their interest in Gaelic tradition at the time of the first Oireachtas.[5] They sound a very pro-active bunch, and seem to have done a lot to encourage tradition-bearer participation in competitions, feiseanna etc. At the forefront of this activity, aided and abetted by two local schoolteachers, was a gentleman identified only as Dr Lynch. If he ever had a first name, it is not recorded here. Besides being the local doctor, he generated various parochial initiatives. One is not told why, although one imagines that their aim was the establishment of a self-sufficient local community. These initiatives included a Gaelic parliament, a co-operative, a manufacturing business, and a local market. I cannot tell you what the co-operative or the manufactory consisted of, or what was sold at the market, or what effect these innovations might have had on the local tradition, because again we are not told. Instead, I am left juggling a lot of questions against a handful of facts.

The book therefore lacks a comprehensible picture of the community into which Mrs Cronin was born, and of the tradition which that community supported. However, it does contain an assertion that local residents met with early and significant competition success at the national Oireachtas, as well as at local feiseanna. Does this intelligence give us a reliable guide as to the vigour of that tradition? I am doubtful, and I have expressed my scepticism over this claim elsewhere in Musical Traditions recently.[6] Here, it should be read in conjunction with what we know of local revivalist interest in the Baile Mhúirne tradition; and with two conflicting statements by Alexander Freeman, an early collector of folksongs of that region. Both are quoted in the book and Ó Cróinín does not attempt to reconcile them. First of all we are told that "Collectors who have worked in other districts of Munster tell me of peculiarities which - as far as my experience goes - are happily unknown in Ballyvourney, such as a shrill harshness in the high notes, a straining loudness throughout the song, or a uniformly dull, nasal, lethargic delivery ..." For objectivity and detachment this ranks alongside Maud Karpeles’ famous observation about her trip through the Southern Appalachians with Cecil Sharp; "We never heard a bad tune."[7] In the world of folk music, who decides what is good or bad: Karpeles, Sharp and Freeman, and those early arbiters of the Oireachtas, whose tastes were moulded by forces external to the folk tradition, or the people who were born into the stuff, and made it and shaped it into the image of their lives and social culture?

The second statement relates to the state of song tradition and of the Gaelic language at the time Freeman was collecting in Baile Mhúirne, 1913 and 1914. “The people I was living with ... told me that I had a mere remnant of the songs of the neighbourhood. ‘For the Irish is gone and the old people are gone, and the songs are gone. If you had come here twenty years ago, then you would have got songs!’” One wonders how, if the language and the tradition were in such a parlous state, did the Baile Mhúirne residents achieve such high standards of performance and such recognition?

What we have unearthed so far is much too sketchy to do anything with. Nevertheless, in the absence of anything more substantial, I am left conjuring images of a number of Gaelic revivalists bravely battling against an ebbing tide of Gaelic language and culture. The gut feeling is that the Gaelic component of the Baile Mhúirne folk song tradition was in decline by the turn of the last century, and that it was revived and remoulded by influences external to that tradition.

I am sorry if that sounds niggly and nit-picking, for I have no wish to rubbish the efforts of people whose aims I find extremely laudable. However, folk tradition and revivalist interest in folk tradition are two separate things. A serious work like this should have tried to keep them apart. It is not beyond the bounds of reason that interest by the doctor, the schoolteacher and various members of the Gaelic League, might have influenced the conscious understanding on the part of the Baile Mhúirne singers of their own tradition. It is perfectly possible that such interest could have ended up redefining the very thing we try to apprehend.

Be that as it may, local interest in the Baile Mhúirne tradition resulted in visits to the area by an astonishing number of musical folklorists and other cultural enthusiasts. No less than twelve song collectors worked in the Baile Mhúirne region in the years between about 1900 and 1943, and they were supplemented by people interested in local wordlore and other aspects of Gaelic culture. These early gleaners are considered in isolation from post world war two field workers, on the grounds that the latter group worked directly with Mrs Cronin. Both are sets of cohorts are discussed in some detail, but the discussions contain some strange comments and some singular uses of English. For instance, I doubt that Dáibhí Ó Cróinín intended the following sentence to mean what it actually says: "The adjudicators of the competition ... remarked that there were a lot of fine songs in his collection, but because the author was unwilling to cede copyright in their publication to the Minister for Education, it never appeared in print."[8]

Hardly had I stumbled over this ambiguity before I found that Alexander Freeman’s collecting work was done, "Before even the great English collector Cecil Sharp undertook his well-known collecting trips to the Southern Appalachian region of the United States". I do not understand what Ó Cróinín means by this. Sharp had been an energetic field worker for about ten years before Freeman ever ventured to Baile Mhúirne, and had amassed well in excess of two thousand songs.[9] However, Freeman was a member of the London Irish elite and a stranger to the Baile Mhúirne district. He was presumably also a stranger to the ways of rustic Gaeldom, at a time when travel to the west of Ireland was by no means as easy as it is now. It may be then that Ó Cróinín is trying to emphasise the expeditionary nature of Freeman’s work. If so, I suggest that he reads Cecil Sharp’s biography, and learns of the privations which Sharp suffered during that travail. A more appropriate parallel could have been made by comparing Freeman’s activities in Baile Mhúirne, with Lucy Broadwood’s collecting trip to nearby Co Waterford in 1906.[10]

I would like to move on, but we are not done yet with the Freeman collection which, by the way, numbers just one hundred and seventy two songs. Despite being of fairly modest proportions it is, Ó Cróinín claims, "perhaps the most famous of all collections of Irish traditional song". What, more famous than Joyce or Petrie, or Sam Henry, or Douglas Hyde, or Eibhlín Bean Mhic Choisdealbha, or Tom Munnelly’s inexhaustible field recording work, or the invaluable work Jimmy McBride has been doing up on the Inishowen peninsula? This assertion so intrigued me that I looked up the entry for Alexander Freeman in The Companion to Irish Traditional Music.[11] An anonymous contributor gives an un-referenced quote from Donal O’Sullivan. It says that O’Sullivan described Freeman’s work as "Incomparably the finest collection in our time of Irish songs noted from oral tradition". I know not where O’Sullivan said such a thing, but it certainly wasn’t in that author’s Songs Of The Irish.[12] There we are told that the Freeman collection is "unrivalled in point of accuracy and erudition". Right. Gotcher. We are not talking fame. We are talking scholarly standards. Unfortunately, fame and scholarship are by no means synonymous - as the present work demonstrates.

The book brightens up considerably when the editor turns his attention to those collectors who worked with Mrs Cronin - Séamus Ennis, Brian George, Alan Lomax, Jean Ritchie and Diane Hamilton. Even here though, quirks and omissions are much in evidence. For instance, Marie Slocombe is not numbered among the quorum, yet she can be heard questioning Mrs Cronin on at least two BBC recordings.[13] Neither could I find any mention of Robin Roberts, although she served as Alan Lomax’s assistant during his fieldwork with Mrs Cronin, and is credited with one of the photographs in the book.[14]

At the start of this section we are told that Séamus Ó Duilearga, who was then Director of The Irish Folklore Commission "conceived a plan to send collectors to the various Gaeltacht areas ... to record ... samples of the story telling and folklore of those areas ..." This refers to decisions taken in 1946. Since the Commission had been founded eleven years earlier, with just this brief, readers may be forgiven for wondering what had changed?

For fear that anyone may be kept awake nights, I will try to explain. The early years of the Commission were characterised by a shortage of funding, and a shortage of quality recording equipment. Field collecting was carried out either by hand notation or by the use of a cylinder phonograph. In the latter case, the recordings were transcribed by the collector, and the material archived in the form of hard copy. The cylinders were then apparently skimmed in a lathe so that they could be recycled. The Commission did acquire a Presto disc recorder in 1940, and this was used to record singers, storytellers, etc. at the Commission’s headquarters, and at the Oireachtas. Being mains powered, however, it was useless for fieldwork in areas where there was no mains electricity. That, almost by definition, meant those areas where folk traditions were at their most vigorous. It was not until 1946 that the Commission acquired a van plus a disc recorder which ran off rechargeable batteries. This development meant that archiving of sound recordings on a large scale at last became a feasibility. Thus, the plan, which Dáibhí Ó Cróinín speaks of, would have referred less to field work practices, than to archiving practices. Incidentally, I am not a Gaelic speaker. Dáibhí Ó Cróinín is, and I presume a highly fluent one. He does not need me to point out that the word area is superfluous when used in conjunction with the word Gaeltacht.[15]

Extracts

from several of Mrs Cronin’s letters are reproduced in this section, as are a

couple of tributes from Séamus Ennis, and there is a copy of a letter home from

Jean Ritchie. Between them they convey a touching and vivid picture, not

just of the collector/informant context, as Kenneth Goldstein called it[16],

or of a fine singer, but of a warm hearted, generous and truly hospitable human

being; someone I would have been privileged to have known.

Extracts

from several of Mrs Cronin’s letters are reproduced in this section, as are a

couple of tributes from Séamus Ennis, and there is a copy of a letter home from

Jean Ritchie. Between them they convey a touching and vivid picture, not

just of the collector/informant context, as Kenneth Goldstein called it[16],

or of a fine singer, but of a warm hearted, generous and truly hospitable human

being; someone I would have been privileged to have known.

Unfortunately, even these delightful touches have their editorial failings. The extracts from Mrs Cronin’s letters include references to the famous Sliabh Luachra fiddlers, Pádraig O’Keeffe and Denis Murphy, and to John Connell, a wonderful singer and near neighbour of Mrs Cronin’s. The first two are footnoted. John Connell, who will be much less familiar to the book’s readers, is not. Also, one of those photographs shows Elizabeth Cronin making a decoration for a wren hunting ceremony. A note of explanation would have helped demystify any readers not familiar with the custom of wren hunting.

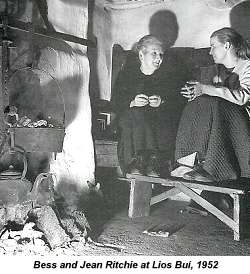

The best of the photographs, including the wren hunting one,

were taken by George Pickow, Jean Ritchie’s husband. They bear evidence of

Pickow’s trade as a magazine photographer and are better judged as pieces of

photojournalism, than as ethnographic record.  Nonetheless,

there is no denying the fine grained graphic detail with which they capture the

humble cottage and spartan living conditions that were rural Ireland in the

1950s. George Pickow presumably photographed all the singers and musicians

recorded on the Ritchie’s tour, and that tour embraced England as well as

Ireland. I suspect therefore that there is room for a very handsome book of

photographic studies of the traditional performers of both countries.

Nonetheless,

there is no denying the fine grained graphic detail with which they capture the

humble cottage and spartan living conditions that were rural Ireland in the

1950s. George Pickow presumably photographed all the singers and musicians

recorded on the Ritchie’s tour, and that tour embraced England as well as

Ireland. I suspect therefore that there is room for a very handsome book of

photographic studies of the traditional performers of both countries.

All the same, there is something rather disjunctive between

the way Pickow’s photographs depict Mrs Cronin, and what little we are told

about her. Elizabeth Cronin came from an educated background. She was

the daughter of the local schoolmaster, a member of a family famed for book

learning, and the mother of a professor of Gaelic. Yet her surroundings,

that bare earth floor, those whitewashed walls, and that wooden bench, have

such a look of poverty about them. The situation becomes clearer when we

learn that Mrs Cronin was staying at her sister’s in nearby Lios Buí at the

time of the Ritchie’s visit. It becomes even more so when we consider the

photograph taken by Robin Roberts’. That one shows the entrance to  Bess’s

home - the intriguingly named Old Plantation - and tells of a skylight in the

ceiling, a solid single piece wooden door, an impressive looking knocker and a

lock with a key in it. In 1951, in west Cork, there can’t have been too

many households affluent enough to warrant a lock and key.

Bess’s

home - the intriguingly named Old Plantation - and tells of a skylight in the

ceiling, a solid single piece wooden door, an impressive looking knocker and a

lock with a key in it. In 1951, in west Cork, there can’t have been too

many households affluent enough to warrant a lock and key.

Back to editorial standards. Lest anyone thinks I exaggerate the book’s deficiencies, all but one of the objections I have so far raised relate to a short introductory narrative of less than twenty pages. There is more to come. For instance, considerable play is made of the recording technology available to the various collectors, and we are told that the Ritchie/Pickow expedition used a portable tape recorder superior to anything the BBC or the Irish Folklore Commission had at that time. No technical details are given. We are told that Diane Hamilton was the last important collector to visit Mrs Cronin, but we are not told who came after her, or if anyone came after her. All we are told is that Sidney Robertson Cowell and her husband, who were collecting in Co Galway in 1956 - 7, didn’t. In case you are wondering why I haven’t mentioned the sections on Mrs Cronin’s adult life and singing style, there aren’t any. In fact, those few sentences of Ewan MacColl's, which I reproduced above, tell us more about her singing technique than does this whole book.

Snippets of biographical information do turn up in various places in the introduction, but they are meagre and few. For instance, the farm she was boarded out to seems to have been a substantial enterprise; substantial enough to employ a number of servants, at any rate, and Bess learned some of her songs from them. But what happened to her after that is a mystery. There is a photograph of her husband, Jack Cronin, but I could not find a single word about him in the text. We are told that her first public appearance was at a feis in 1899, which she entered with a cousin of hers, Julia Twomey. Bess’s contribution was apparently well received, but we are not told whether she or Ms Twomey won anything. Nor are we told of any subsequent public appearances. How is it that a singer who described herself in the following terms, managed to escape the attention of such a wad of collectors until 1935:

“I sang here, there and everywhere: at weddings and parties and at home, and milking the cows in the stall, and washing the clothes, and sweeping the house, and stripping the cabbage for the cattle, and sticking the sciolláns [seed potatoes] abroad in the field, and doing everything.”[17]

Could it be that sang is the operative word? Could it be that she was a victim of what Herschel Gower and James Porter call gender ideology; that process, which they claim as common to many folk traditions, where women performers become marginalized during the period between marriage and middle age?[18]

By the way, I did say 1935 just then. Failure to read the entire introduction carefully could leave you with the impression that Mrs Cronin was not discovered until Séamus Ennis and Brian George visited her in 1947. That is because the section which deals with collectors who worked with Bess Cronin dates from 1947 and George and Ennis are the first collectors discussed. However, when the reader works through to Appendix 1, he or she will find a Gaelic recitation which Proinsias Ó Ceallaigh of the Irish Folklore Commission noted from her twelve years earlier.

Turn back to the introduction and you will find that Mr Ó Ceallaigh is indeed mentioned, but not in the section which details people who worked with Mrs Cronin. He is lumped in with those early collectors, the ones who, by implication, didn’t. Please do not blink, because this historic meeting is dismissed in just seven words! Those seven words do however inform us that Proinsias Ó Ceallaigh noted some songs from Mrs Cronin. By now, it should be no surprise to learn that we are not told what they were. You will, it is true, observe another appendix immediately after this recitation. It consists of a list of songs collected in Baile Mhúirne and compiled by Proinsias Ó Ceallaigh. The only problem is that it relates to the work of another collector, one Micheál Ó Briain. The reasons for including this list have been lost upon me, especially as Ó Briain’s collection has also been lost, and either Ó Briain or Ó Ceallaigh or Ó Cróinín omitted to say from whom the songs were collected. Also omitted is a proper summary to show us just who collected what. The book does contain a tabulation of collected items which lists titles, record indices and the recording dates; the latter being shown as closely as institutional record keeping has allowed. Unfortunately, it does not identify the various collectors.

It just goes on and on. That section concludes with a brief mention of Dáibhí Ó Cróinín’s father and uncle, Donncha and Seán Ó Cróinín. Dáibhí Ó Cróinín tells us that, since they number among the collectors who worked with Mrs Cronin, they are best included in the latter section. Fine. I agree. Where are they? We are told that the BBC recorded a recited version of Lord Gregory from an old woman in Scotland, but no reference is given.[19] In the notes to the Capabwee Murder, the location of the outrage is specified, as are the names of the protagonists. The date is not. The introduction reproduces the piece of actuality, given above, in which Bess describes to Alan Lomax where and when she used to sing.[20] According to the footnote this, and several similar pieces can be heard on the Columbia World Library volume covering Ireland. I am sorry, but I have owned a copy of that record for donkey’s years and I can assure him, that particular piece of actuality is not on there. Neither are the other bits he mentions. The only words spoken by his grandmother on the entire disc introduce her song, Cuckanandy, and then relate the difficulties of translation. Things like this make me seriously wonder whether Dáibhí Ó Cróinín went to the bother of listening to some of the materials to which he refers.

On one page he correctly gives the date of the founding of the Gaelic League as 1893. Then, immediately overleaf, he says it was 1897. Mr Ó Cróinín, by the way, is a professional historian. He practices at the Galway campus of the National University of Ireland. In discussing previous attempts to issue Mrs Cronin’s singing on commercial record, he summarises the brief career of Leader Records, with one or two minor errors. To be fair, these are possibly due to failing memory on the part of his informant, Dave Bland, who used to work for Leader, and this type of evidence is better collected from record company files than from an oral source. However, it is regrettable that the attention given to the rise and demise of Leader Records has not been replicated in sections more germane to the immediate subject matter.

I wish I could report that Mrs Cronin’s song repertoire was better served, but I cannot. As mentioned earlier, the adopted format for each song consists of text and title, plus a melody where one is known. There are English abstracts for each of the Gaelic texts, and both English and Gaelic songs have explanatory notes. Besides being shown in the summary I mentioned earlier, recording dates and archive reference numbers are identified here also.

All well and good. The problem is that Dáibhí Ó Cróinín supplements the collected texts of Mrs Cronin’s songs in four different ways, three of which I regard as methodologically questionable. They are: listing of verses which Mrs Cronin remembered subsequent to being recorded; source listings of alternative song versions; comparative variant analysis; and interpolation of printed texts. With the first of these, there is clearly no argument. Whatever verses Mrs Cronin sang deserve to be in the book, irrespective of where or when she remembered them. Regarding his source listings, however, the song notes list titles of printed collections which contain versions of Mrs Cronin’s songs, as collected from other singers. This, he tells us, is for the benefit of readers who wish to compare Mrs Cronin’s settings with "the general body of Irish traditional song". There is probably not a lot of point in my objecting that ‘the general body of Irish traditional song’ varies to such an extent that one cannot make meaningful comparisons in this fashion. This becomes even more so, where his listings include international analogues.

Instead, I shall point out that Ireland is woefully under-served in terms of reliable and scholarly printed song collections. That is certainly so in English. I doubt that the situation is all that much better with Gaelic. It is however extremely well represented in terms of field recordings of singers like Mrs Cronin; even if most of the material remains stacked away in libraries and archives. However, given the low profile of the CDs in this book, it should come as no surprise to discover that he lists very few audio sources. If a decent audit of sound recordings of versions of Mrs Cronin’s songs had been carried out, readers could have extended their exploration to discover how her performances compared with those of other singers.

That 'if' could be a rather big one, for Dáibhí Ó Cróinín seems to have a whimsical way with compilations. For instance, despite the fact that Green Brooms has not been collected very often in Ireland, his list of printed sources does not include the version which Sam Henry obtained in Ballycastle, Co Antrim. Instead, he directs the reader to a Folkways LP by the American revival singer Paul Clayton. This is on the grounds that Clayton’s song came originally from Co Longford. I trust that his interpretation is as collected, word for word and note for note, for anything less would undermine Dáibhí Ó Cróinín’s stated objective. It is certainly undermined in the case of Marrowbones, where he directs us to Stephen Sedley’s notorious compilation of collations, The Seeds of Love. The reason for this, apparently, is that the elements from which Sedley re-stitched the version published in that book, ""are from Irish oral tradition, collated with a copy in the Sam Henry collection". The quote comes from Sedley, not from Ó Cróinín, so we need not trouble to wonder what the Sam Henry copy represented, if not Irish oral tradition. We may though wonder why Ó Cróinín bothered to mention Sedley’s collation when his very next sentence refers the reader to the said Sam Henry set.[21]

With reference to variant analysis, his notes in some cases incorporate additional verses which have been taken from printed collections. These are either variants of, or supplements to, the ones which Mrs Cronin sang. I am at a loss to understand why he should have considered this necessary. In the vast majority of cases, Mrs Cronin clearly regarded these songs as complete or she presumably would not have sung them. Therefore, while making due allowance for ageing memory, if we are to understand the repertoire of Mrs Elizabeth Cronin and what these songs meant to her, then we have to regard the songs as complete in themselves. To take a single instance, the fact that Sparling’s Irish Minstrelsy contains a version of The Croppy Boy, with the verses in a different order, and with two additional verses and minus one of Mrs Cronin’s, may be relevant to a study of The Croppy Boy. At least, it would be if Sparling's Irish Minstrelsy were a reliable source, which it isn't. In any event, irrespective of whether the source material can be verified, this kind of comparison is irrelevant to a study of Mrs Cronin’s repertoire.

If that were the end of the matter, I would not complain too loudly. The listing and comparing of versions is a legacy from the days when folklore studies was a branch of comparative social anthropology. On its own it is a rather fruitless activity, but is at least fairly harmless. However, it was the use of interpolated texts which had me tearing my hair out. These interpolations arise because, while Mrs Cronin’s repertoire is summarisable, it is not entirely identifiable. That is to say that it has been assembled from disparate sources. Part of it comes from sound recordings and part from assorted hand-written texts made by Séamus Ennis, by Dáibhí Ó Cróinín’s father and uncle, and by Mrs Cronin herself. In addition, however, she compiled a list of titles and in a substantial number of cases the title is all that has survived. Ó Cróinín has therefore tried to fill in some of the missing bits of the repertoire by recourse to printed collections. He tells us that, "In a few instances, where the title of a Bess song has survived, but no known sound recording or transcription, I have given a text which I believe is what she would have sung, but which I have only from the singing of another family member or from a neighbour". It behoves me to point out that wherever interpolations are included, they are incorporated in the notes, their source is identified, and they are clearly distinguishable from Mrs Cronin’s own texts. Therefore, if these missing bits had indeed been gathered from clearly identified family and neighbours, that would have been a job well done. In fact, I could not find a single instance where a song, or part of a song is labelled as having been recovered from a neighbour or a relative. As far as I could see, they have all been taken from published sources. For Roll On, Silvery Moon, for example, he prints two verses from Fitzgerald’s Account of the Old Street Ballads of County Cork, followed by two verses from Walton’s Treasury of Irish Songs and Ballads, followed by a verse from Alfred Williams’ Folk Songs of The Upper Thames, followed by a verse from McLaskey's 200 Favourite Songs. All this without any supporting evidence whatsoever that anybody ever heard her sing verbatim those verses in that order.

Does this tangled trail really add up to what Mrs Cronin sang? If by some strange chance it did, what do we say about that curiously titled, Little Girleen with the Curling Poll, Would You Buy Brooms? Ó Cróinín’s accompanying note tells us that this is "presumably the well known song Cutting Down Brooms", which Séamus Ennis noted by hand from the famous Conamara singer, Seán ‘ac Donnchadha in 1947. He then prints Ennis’s 1947 text of ‘ac Donnchadha’s song, as though it were entirely cognate with Mrs Cronin’s, even though differences of scansion and metre suggest otherwise. Incidentally, there is no glossary of terms with this book and Ó Cróinín does not explain what is meant by a curling poll. However, it does, I believe, mean short cut curling hair

It is odd that Mr Ó Cróinín refers on several occasions to the LP series, The Folk Songs of Britain, for he does not appear to have noticed that Seán ‘ac Donnchadha sings Cutting Down Brooms on Volume 3. At any rate, he does not mention the fact. However, his notes to this entry refer to a version of it in Peter Kennedy’s Folksongs of Britain and Ireland without naming the singer. I looked it up. It was recorded by Alan Lomax and Séamus Ennis in 1951 from the self-same Seán ‘ac Donnchadha. It is the version which appears on Jack of all Trades, and to all intents and purposes it is the same as the one he has just printed.[22] Nor can he get the date of issue of The Folksongs of Britain right. Topic Records of London did not bring this series out in 1961. Caedmon Records of New York did. Topic did not begin to release them on this side of the Atlantic until 1968. I know, because their appearance over here coincided with a nascent awareness on my part of the importance of singers like Mrs Cronin. They were part of my education.

To appreciate how closely Ó Cróinín’s methodology resembles the pinning of the tail on the donkey, take a look at the note for entry number 99; My True Loves’ Face is As Bright. It is worth quoting in its entirety. Please read carefully.

Title only from one of Bess’s song lists. Tom Munnelly writes ‘Perhaps the English language version of An Droighneán Donn. On the other hand, it could be anything.’ Alternatively, it could perhaps be the song called The Cailín Deas (“My true love’s eyes are as bright”) published in JIFSS 19 (Dec 1922) 44-45.

Thus, assuming that he is right and Munnelly is wrong, Ó Cróinín, prints four verses of The Cailín Deas as they appear in the Journal of the Irish Folk Song Society for 1922.[23] Who collected these verses and where from? Were they noted by Alexander Freeman or Seán Ó Cuill, both of whom worked the Baile Mhúirne district before 1922? Are they local to Baile Mhúirne and, if they are, does that give us some basis for assuming Bess Cronin sang them? There is absolutely no way of assessing these questions because Ó Cróinín does not take the elementary step of identifying the collector and does not say where the song comes from. Moreover, I have checked the bibliography from start to end, and fine indeed were the teeth of my comb. There is no JIFSS article listed for the year 1922. Neither, although the text refers elsewhere to some of Seán Ó Cuill’s songs having been published in that organ, could I find his name in the bibliography.

I can’t say that I checked his alternative versions or his interpolations much beyond this point. However, I did notice a strange anomaly concerning the dandling song, The Little Pack of Tailors. In the accompanying note, Ó Cróinín tells us that, for some undisclosed reason, John Moulden directed him to a variety of LP sources. I do not know the reason, and I do not know what is on Decca SKC 5287, for I was never a fan of Johnny Moynihan. However, nothing remotely resembling the melody or text of The Little Pack of Tailors can be found on Topic 12TS 334, Tradition TLP 1004, or XTRA 5041. If John had simply pointed out that the melody of The Little Pack of Tailors is a version of the reel, The Wind That Shakes the Barley, it might have sent Dáibhí Ó Cróinín off in the direction of Michael Coleman’s record of that tune. Whilst searching through the legacy of Coleman recordings, he could have taken a look at the way Harry Bradshaw turned oral and written testimony into a comprehensive biographical study of the man. It comes with the Gael Linn double CD of Coleman. The entire package is a fine piece of work and the biography would, I respectfully suggest, have made a propitious model for the present enterprise.[24]

It was with great relief that I turned to the CDs; except that track 1 of CD1, Níl Mo Shláinte ar fónamh, begins with a piece of actuality which relates to the song’s composer, and the trials he had fending off the drink. It is not mentioned in the track listing and I could find neither reference nor transcription anywhere in the book! In track two, The Lover and Darling, I noted seventeen inaccuracies in the transcription. In track 3 - Cuckanandy - two verses have become transposed, “here” is misspelt as “hear”, and a line which appears on the record as "He didn’t dance, dance, no nor yesterday" is mis-transcribed as ‘He didn’t dance, dance, he won’t till after tea’.

There is no sense in entering into a blow by blow account of every transcription error. Like the poor, they seem to be permanent and plentiful. However, my tolerance was stretched to breaking point on listening to There Was A Lady In Her Father’s Garden. It is accompanied by a note to the effect that Bess accidentally missed out the first half of verse three, when she sang it into Jean Ritchie’s tape recorder. The offending fragment has therefore been eliminated from the published transcription, and included with the song notes. Ó Cróinín doesn’t say how it was come by, but otherwise, that is good practice and one cannot argue with good practice. Anyway, in the light of this intelligence, one would not expect to find that half verse on the disc. Indeed, remembering that this is the only extant recording of Elizabeth Cronin singing There Was A Lady In Her Father’s Garden, it should be impossible to reproduce the said half verse on this sound clip. (N.B. Fred’s original review for Musical Traditions included a number of sound clips – Ed.)

Believe me, my friends, there was nothing up my sleeve. I did not conjure that out of the ether. I did not follow the example of a man who is supposed to have walked the streets of Hamburg, recording barking dogs, until he had enough elements from which to synthesise a complete choir of them barking Hark the Herald Angels Sing.[25] It is on the CD, right where it ought to be. Bess Cronin did not forget to sing it.

Where the problem has arisen, I think, is that Bess sang this to one of those eight line melodies, which consist of two very similar parts; the main distinguishing feature between the two being that the opening line of the second is a variant of the opening line of the first. In several places she confuses the two parts and this in turn appears to have confused the transcriber. Can her doing so be considered a mistake, or a feature of oral tradition? I don’t know, but I’ve heard other singers do the same thing. However, a golden rule of folk music notation could usefully have been applied here; regard whatever the singer sings as correct.

Could Dáibhí Ó Cróinín could be combining texts from different sessions? Apparently not, even though a good proportion of the songs were noted on more than one occasion, and I suspect that some of Mrs Cronin’s performances varied quite a lot. Nevertheless, he is quite specific. Each transcription comes from one source and one source only, and that source is identified in the note which accompanies the song. Mrs Cronin did sometimes recall additional verses, subsequent to being recorded. However, as ostensibly happened with our ‘missing half of verse 3’, these recalled verses are embodied in supplementary notes. Moreover, where a song appears on one of the CDs, that is the text which is used. Therefore, there should be absolute concordance between what one hears on the CDs and what one sees in the book.

Will someone please tell me then, what went wrong with the transcription of All Ye That’s Pierced By Cupid’s Darts? Eight verses are printed in the book, and the source note says that the text used is that of BBC recording 19026. However, BBC 19026, as it appears on the CD, has only five verses. They come in the book’s running order 1, 2, 4, 5 and 8!

Before this damned book drives me mad, as Spike Milligan almost said of Puckoon, let me get back to telling you about the discs. They have been compiled and edited by Nicholas Carolan and Glenn Cumiskey of Taisce Cheol Dúchais Éireann (The Irish Traditional Music Archive), and remastered by Harry Bradshaw of RTÉ. They consist of fifty-nine tracks, which comprise a little under one third of her known repertoire and about one half of all the songs recorded from her. Generally speaking, the recordings have responded to digital transfer very well indeed. The worst of them without question are the CBÉ disc recordings.[26] Yet even these come nowhere near the depths of inaudibility, which all too often characterises CD transfers of similar material. The first disc consists of nine tracks from Séamus Ennis’s 1947 CBÉ recordings, together with a range of BBC material, which Ennis recorded with Brian George and/or Alan Lomax in 1947, 1951 and 1952. None of the 1954 recordings have been included, one guesses, because of Mrs Cronin’s poor health at the time. The second disc is comprised mainly of Ritchie/Pickow material with one track from Lomax’s 1951 visit, and four from Diane Hamilton. As Nicholas Carolan’s note on the CDs points out, what comes out of the collector/informant context to a large extent depends on what the collector is looking for. Hence, Ennis’s knowledge of Gaelic, compounded with the brief of the Ritchie/Pickow brief expedition, mean that there is a far greater partiality towards Mrs Cronin’s native language on the first disc than on the second; Gaelic songs accounting for 57% of disc 1, but only 17% of disc 2.[27]

I confess, I found myself struggling with the songs as Gaeilge. That is not just because of language difficulties on my part. It is also because, for the most part, they are local creations, which seem to draw little upon a wider geographical stock. Of the twenty-two Gaelic songs on these CDs, a non-specialist audience may recognise Níl Sé Na Lá (It’s not the Day) and Cois Abhainn na Séad (By the River of Gems). This latter is local to the Baile Mhúirne district. However, it gained an international audience through a famous, but abruptly edited, fragment which appeared on volume 1 of the Folk Songs of Britain. It was sung on that disc by Máire Ní Cheocháin of neighbouring Coolea.[28]

The book lists two different songs under the title Seoithín Seó, and one of them is a rare gem indeed. Seoithín Seó is a fairly generic title for lullabies, and to avoid confusion, we may as well adopt the designation used by Donal O’ Sullivan. He called it A Bhean Úd Thíos Ar Bruach an tSruthain (O Woman Washing by the River).[29] This curious song of a fairy kidnapping, in which the victim sings a plea for help in the form of a lullaby, does not appear to have travelled outside of southwest Munster.[30] I would think that the song’s interesting story and splendid melody make it worthy of a wider circulation. As well as the two Seoithín Seó lullabies and the aforementioned dandling songs, there are various other examples of occupational and functional songs. There is a partly Gaelicised version of Rock-a-bye Baby, a topographical song whose verses were originally extemporised by various members of a wedding party, and there is even a milking song. When one considers the paucity of Irish occupational songs, compared to the Hebrides, these items become all the more significant.

The English summaries, brief as they are, left me plenty of room for rumination. In sentiment at least, a number of the Gaelic songs seem to hark back to an earlier and different era of Gaelic poetry; to a time when the edicts of Cromwell were depriving the professional poets of income and patronage. In several compositions, Níl Sé Na Lá is an instance, the poet falls foul of the drink, and of the pub landlady; and they echo Dáibhí Ó Bruadair’s famous diatribe against a servant woman who refused him a drink.

A shrewish, barren, bony,

nosey servant

Refused me when my throat was parched in crisis.

May a phantom fly her starving over the sea,

The bloodless midget that wouldn’t attend my thirst.[31]

Other parallels with the poetry of dispossession can be found in Seothó-leó, a thoil, where the poet laments the fact that his poetry is no longer respected, and in Mo Leastar Beag (My Little Firkin), in which the poet hauls his butter to market, only to have it rejected by the butter taster. They respectively reminded me of another composition of Ó Bruadair’s; D’aithle na Bhfileadh (The High Poets are Gone) and of a poem by Mathghamhain Ó Hifearnáin who lamented the fact that, since his patronage had been dissolved, he couldn’t even sell his poetry around the marketplace.[32] The days are thankfully gone when folklorists and literary scholars - Anglophones, at any rate - viewed folk art and poetry as something exclusive to the high deeds and high drama of European balladry. Nevertheless, to anyone unacquainted with Gaelic culture, it may seem odd that skilful song makers would have wasted their time on such apparent trivia. But therein lies the genius of the thing. It was W B Yeats, I think, who observed that the history of a people is written not in wars and conquests, nor in the accomplishments of kings and politicians, but in the day to day affairs of the unexceptional: in how ordinary people fought and loved and lived and laughed; about how they wrought with life and sometimes won and sometimes lost; and how they fell foul of the butter taster and the shrewish, barren, bony, nosey servant, who meted out the drink.

There are several macaronics on these discs, two of which I have not heard before, at least not in these versions. The first is an awesome rendering of An Bínsín Luachra (The Bunch of Little Rushes), which destroys me every time I listen to it. I am familiar with Gaelic sets of this song, and it has been the subject of at least two separate folk translations, but I cannot recall hearing it in macaronic form before.[33] Mrs Cronin sings it not to the usual Bínsín Luachra melody, but to the air of The Buachaill Rua. An unusual tune perhaps, and one which does not always scan very well. Yet it somehow fits the song like a glove and the metric discrepancies give Mrs Cronin plenty of room to throw in some superb ornaments. Abhainn na séad? Níl ceist!

The second, Taim Cortha Ó bheith am’ aonar im’ lúi, is even more intriguing, for it turns out to be a version of I’m Weary of Lying Alone. Ó Cróinín points out that that this is an English song, whose English verses are paralleled by equivalent verses in Gaelic. Folk translations between either language are fairly rare and this one runs counter to received wisdom; namely that macaronics were made at a time when poets were starting to use English, but were insufficiently fluent to compose entire songs in that language. Here is an example of a poet who knew English well enough to translate a complete song into Irish. It suggests to me that macaronics existed not because poets suffered from any linguistic deficiency, but because some at least were linguistically ambidextrous and wanted to display the fact.

But it was the English language songs which, by virtue of quality and geographic diversity, took me by storm. For quality look further down the page. For geography, look immediately below.

Among the songs in English, there is the usual spread of local and pan-Irish compositions and there are quite a few which owe their genesis to England. There is also a number of songs, principally Lord Gregory, The Bonny Blue Eyed Lassie, and The Braes of Balquidder, which seem to show strong Scottish connections. The evidence is slender and I do not wish to overstate it, for the routes taken by migratory songs are often impossible to predict or to follow. Nevertheless, I quietly wonder whether the connection might be less with Scotland than with Ulster. The Braes of Balquidder and The Buachall Rua, are both similar to Ulster versions, while One Pleasant Evening as Pinks and Daisies, The Factory Girl, The Boy in Love that Feels No Cold and The Lass Among the Heather, are all found in that part of the world.[34] To cap it all, the only other version I know of The Irish Jubilee to have been collected on this side of the Atlantic, was turned up by Robin Morton in Co Armagh.[35]

An uncle of Elizabeth Cronin’s was in the habit of putting up beggars and travellers as an act of charity, and Bess acquired a number of her songs from such people. Did one of them chance to wander all the way from their Ulster homeland down to west Cork? I know not, but the possibility may explain a riddle which has intrigued me for years. It relates to similarities in poetics and sentiment and verse structure between The Charming Sweet Girl that I Love and Erin the Green. The first of these appears to be unknown outside of the district of Macroom, while the provenance of the second seems restricted to the Rosslea district of Co Fermanagh. It is true that the first song is a man’s complaint of unrequited love, while the second relates the story of a girl who has been abandoned by her lover. However, spurned or unrequited, the makers of both songs included a verse imploring ballad singers to carry the sentiments of their ballad to their loved one’s ears. This motif is sufficiently unusual to make me think that one song might have been modelled on the other. Compare the following:

Erin the Green

Oh there's one request I crave, though my mind it's in vexation,

This song should be sung everywhere,

And although he's abroad in some far distant nation,

My sorrow might soon reach his ear,

And when that he hears for his absence I mourn,

I am sure that with full speed my true lover he'll return,

And never again his kind offer will I scorn,

But I'll wed him in Erin the Green.[36]

The Charming Sweet Girl that I

Love

If my song it were sung by that worthy good man Haly,

it would soon find its way to Macroom;

And it's there 'twould be purchased at fairs and at markets,

where young men and fair maids are in bloom.

Where songsters they would sing it with voices long and loud,

And who knows but my dear darling might chance to be in the crowd

Oh! it's then that I would sigh and I’d say in a shout:

"How I long for the girl that I love!"

Both songs were, incidentally, sung to the air of Uileachán Dubh Ó. Ó Cróinín does not identify ‘that worthy good man Haly’, although he crops up in quite a number of the references. The name in fact refers to a ballad printer, who was active in Cork from the 1820s to the 1850s, and who disseminated a fair number of politically subversive ballads among the populace of southwest Munster.[37] Surprisingly, political songs do not figure much in Mrs Cronin’s repertoire; unless one counts her Napoleonic ballads, of course, and the ubiquitous Croppy Boy. Less surprisingly, Taim Cortha Ó bheith am’ aonar im’ lúi apart, there is virtually nothing here which could be deemed at all risqué. Otherwise, her repertoire is distinguished by a remarkable eclecticism, and a rare quality of discernment.

Eclecticism? Well, she didn’t have too much in the way of Child ballads. A drastically attenuated Barbara Allen, a stock version of Lord Randall which she didn’t like very much, a Well Sold the Cow which whimsically locates the action in Yorkshire; and a dazzling re-casting of Lord Gregory almost exhaust the canon. Otherwise, scanning these pages, I felt like a five year old let loose in a candy store. There is an excellent version of the Derby Ram, with several unusual verses, and a melody which has somehow got its fleece tangled up with the jig tune, Hurry the Jug. There is the wonderfully wacky On Board the Kangaroo. There is an appealing version of Froggie Went a’Courting, a fanciful Pussycat’s Party, and an outrageously funny parody of After the Ball.

If I could summon up any confidence in these transcriptions, I would recommend this as a source book for singers. I would also recommend it as an example of a highly personalised repertoire, for I strongly suspect that Mrs Cronin was what she sang; that the range of sentiment which is revealed here represents what Mrs Cronin thought and felt, and that the emotions in these songs should not be considered in isolation. Folksongs represent a form of emotional catharsis which functions by dramatising people’s emotions, but they do not do so on an individual basis. Rather, they work in tension. Or, rather, they present us with varying degrees of light and shade. Here, then, are sentimental songs, tearjerkers like The Miner’s Dream Of Home - with the singer’s country of origin neatly transposed to Ireland - and they lie side by side with lively, jiggy songs like The Kerry Cow, and I Have a Bonnet Trimmed with Blue, and What Would You Do if You Married a Soldier? There are songs which tell of the anguishes and the pleasures of courtship, and there is The Lover and Darling, which satirises the whole business as only Irish poets know how. The darkest of feelings are there in full measure. Yet they are countered by such a wonderful sense of fun, that once again, I am vividly reminded of something by W B Yeats. It is that verse in The Fiddler of Dooney where he says:

For the good are always the merry,

Save by an evil chance.

And the merry love the fiddle,

And the merry love to dance.

There are several songs which, in other versions, made me nostalgic for the high water of the British folk revival. There is her High Germany which has become bound up with The Banks of the Nile, and Whiskey In the Jar, and something which Bess called I Am a Maid that Sleeps in Love. You may recall the song better from the days when Bert Lloyd and a few others used to sing it under the title Short Jacket and White Trousers. For aficionados of English folksong, though, the final item on disc two has to be the most delightfully incongruous of all. For once, Ó Cróinín does not list any alternative sources. However, if you’re wondering, Cecil Sharp collected a version from Mrs Beechy of Shipston-on-Stour, Warwickshire on 22 August 1911.[38]

And there is Lord Gregory. If any single song in this most remarkable of repertoires scoops all the Oscars, this must surely be it. I am not terribly interested in the fact that Elizabeth Cronin had at last furnished the BBC with a melody for the song. Melodies for Lord Gregory have been turned up in the USA, in Canada and in Scotland. Indeed, Jean Ritchie, who was responsible for the recording of Lord Gregory used on these discs, has her own version. She calls it Fair Annie of Lochroyan.[39] Moreover, the melody which Mrs Cronin uses is not unique to the present text. It is associated with several versions of The Shooting of His Dear.[40]

What is significant, however, is the way the text has been restructured to accommodate the sexual mores of the Ireland Mrs Cronin grew up in. In its older forms Lord Gregory is a very long ballad, which moves through several episodes before culminating in the girl’s death by drowning. In some versions, Jean Ritchie’s is a case in point, Lord Gregory commits suicide when he learns of her fate.

In Mrs Cronin’s version, the action centres around just one scene. The girl stands at the castle gates, the illegitimate babe dying in her arms, while she begs and pleads for admission. She is refused by Lord Gregory’s mother and she leaves. We do not know what happens to her. We only know that when Lord Gregory discovers his mother’s treachery, he vows that he will not rest until he can “find the Lass of Arrams and lie by her side”. Why? Why is the ballad so truncated, and why does this version obviate the more usual and more tragic ending? Why is the mother viewed as the traitor, and why, in a ballad which puts out several clues that the subject is a fallen woman, is so much weight, and sympathy, given to her plight? Remembering the moral climate in which Mrs Cronin’s Lord Gregory existed, we might expect the ending to be retained intact as an example to others.

The answer does not lie in the supposed tendency of the Irish to turn every single narrative ballad into a lyric. Enough examples of balladry, native and imported, exist to demonstrate that the Irish are perfectly capable of handling narrative material. Nor is it the case that folksongs existed as integrative mechanisms to reinforce codes of social behaviour. If we try to interpret Mrs Cronin’s version of Lord Gregory in normative or didactic terms, it does not make sense. Far from legitimising, or explicating, social codes, it is truer to say that folksongs existed as a means of enabling people to live under those codes.

Rural Ireland, until very recently, had harsh canons of sexual conduct. Association between unmarried individuals of opposite sexes was rare and frowned upon. If it happened that a girl found herself pregnant out of wedlock she could expect to be shown the door by her parents. In a land where arranged marriage was common enough to be considered the norm, and where marriage was constrained by inheritance and property rights,[41] she could expect no sympathy from her own family and even less from the family of her seducer. She might as well go and drown herself. The fact that she does not appear to do so, and the fact that Lord Gregory vows to ‘lie by her side’, i.e. to marry her, suggests that Mrs Cronin’s version both dramatises the dilemma of non-marital pregnancy, and offers an emotional solution to the dilemma.

On the question of the psychological function of folksongs; another recent Musical Traditions posting of mine contemplates the functional differences between pop song and folk song at some length.[42] Here you can forget the convoluted arguments. Forget the high falutin’ rhetoric. Just find me a single song in the entire realm of pop music which says as much about human feeling and frailty as this does. Find me one single line in the entire output of Tin Pan Alley which cuts half as deeply as does the last line of the first verse of this song: “The babe is cold in my arms, Lord Gregory let me in”.

And when you’ve done and finished this work, go round me up one pop singer in the prime of life who can inject into their performances one tenth of the conviction which Mrs Cronin puts into this. If by some rare chance, you have never heard Elizabeth Cronin sing Lord Gregory, you will not be wasting your money if you buy this entire package for that one track.

Ó Cróinín’s transcription of this ballad is as shot through with errors as the ones I mentioned earlier. However, comparison of the recording on these CDs, with the one used for The Folk Songs of Britain gave me quite a bit of food for thought.[43] That one was made by Alan Lomax and/or Séamus Ennis on 29 August 1952. The present rendering comes from the Ritchie/Pickow expedition and was cut on 24th November of that same year. That is less than three months later, yet there are a significant number of differences between the two texts. There are a couple of verses which appear in one recording, which either don’t appear in the other, or show up somewhere else in the song. The “leave now these windows” refrain appears and reappears so often that Mrs Cronin seems to be incorporating it at will. In the Ritchie’s recording, although not in the Lomax, Bess sings the second half of verse 1, as in the sound clip, and then inserts it as a stand alone between verses 7 and 8. How do we explain this? Failing memory could be a reason for the verse flow, but would hardly account for the irregular appearances of the refrain. Is it a formula; that technique, described by A B Lord, where performers of sung epics insert memorised pieces of text as resting places between stretches of improvisation?[44] That is something I’m inclined to doubt, because I do not think that Mrs Cronin was improvising, at least not in the sense that Lord’s south Slavic epic singers improvised. Rather, I’m inclined to think that it’s more in the nature of what the pop music industry calls a ‘hook’; a ‘relatively independent memorable element within a totality’.[45] That is, a device which is designed to keep the listener listening.

Hook or formula, the whole thing is imbued with such fluid quality, that I view Elizabeth Cronin as an exemplar of oral tradition. That is to say, she did not think of songs as fixed texts, which had to be delivered word for word and verse for verse. Instead, for something like Lord Gregory, she may have had a stock of verses which she strung together more or less as the fancy took her. If so, that could explain her habit of recalling verses after collectors had left. It does not of course explain the transcription errors I discussed earlier.

Bess was literate in English, although not apparently in Irish, and Ó Cróinín is at some pains to stress that her songs were learned entirely from oral sources. On the face of it, the point is not terribly important. She would not have been the first traditional singer to learn songs from print. Moreover, the example of ‘that worthy good man Haly’, is evidence that she was touched by broadsides, even if only indirectly. Nor would she be the first literate woman to learn songs orally. In fact, Mrs Cronin, with her educated family connections, reminds me of Mrs Anna Brown of Falkland, an extraordinary bearer of folk tradition, who was both the wife of a minister and the daughter of a university professor. David Buchan, in his study of the balladry of north east Scotland, opined that Mrs Brown, although a literate and educated woman, was able to operate as a re-creative folk performer because she was mentally and culturally rooted in the oral creative processes of the folk. That is, her approach to ballad performance was non-literate, and therefore non-constrained by the written word.[46] Am I being overly fanciful, if I see something similar in Mrs Cronin and in the way she has woven this ballad? Is she a late justification for Buchan’s thesis? It would take an exhaustive comparison of the results of these field trips before one could pronounce, but the thought is there. The thought is also there that background might have exerted another influence. Did the sway of education, intelligence, call it what you will, set within the matrix of oral culture, induce in Mrs Cronin an uncommon sense of discernment when it came to assembling a repertoire?

I want to discuss Mrs Cronin’s sense of discernment in terms of how she sang these songs. Before I do, however, there is one other aspect of her repertoire I have not so far tackled; namely her local songs in English. As a rule, I am wary of local songs, for the term frequently turns out to be a metaphor for not-very-well-written. Here, there is only one local song which I would regard as less than satisfactory. That one is The Capabwee Murder; a hack composition which, for all I know, may have rolled off the press of ‘that worthy good man Haly’. Most of the other local compositions show a vivacity of rhetoric and a torrent of hyperbole, which people unacquainted with Irish folksong may find astonishing. The following is from The Lover and Darling.

If you were to give me all ships on the main,

Britannia’s powerful dominions,

With Prussia and Turkey and fertile Lorraine,

and also the East and West Indies.

If you were to give me Hibernia of old,

Or were you to give me great trunks full of gold,

Such comical things could my senses blindfold,

And for such I’ll not call you my darling.

If the test of a good song is how easily the words roll off the tongue, then these are very good songs indeed. I cannot detect a great deal of Gaelic influence in most of them, although I am possibly not the best person to judge. However, their sheer fluidity of language hallmarks them as the work of poets who were steeped in the efflorescence of Gaelic. According to an old Gaelic tutor of mine[47] the word blarney does not derive from a rock in the castle of that name in Mrs Cronin’s home county. It is a corruption of the word blathanna, which means flowery. Hence, an eloquent talker in Gaelic, someone who can make extravagant use of the verbal nuances of that language, is said to have the blathanna; a flowery tongue, in fact. If so, then I am left wondering whether blathanna might have some etymological connection with the term blas. That is the expression which Ewan MacColl applied to Mrs Cronin’s singing style in that headline quote. It means accent and is frequently used to describe ‘correct’ or ‘good’ or ‘eloquent’ Gaelic. However, it also means taste or flavour, and in that sense it can be applied to anybody who has a cogent singing style. Did Mrs Cronin have the blas?

It is widely known that she was old and in varying states of poor health when these recordings were made. Assessment of her singing, or rather what we know of it from these recordings, has to be made with that information in mind. Indeed, throughout both these discs the voice is enfeebled, and there are obvious breathing difficulties, and there are many places where she has to pause while she gets her wind back. The situation is exacerbated because her voice seemed to become progressively weaker as time went by. Generally speaking, she is at her best on those early CBÉ recordings, even when the singing occasionally seems lost in a primordial soup of crackle and hiss, and she is at her most exhausted on the better quality Diane Hamilton recordings.

For this reason, I don’t think the producers have served their public all that well in the way they divided these discs up. As I mentioned earlier, CD 1 is comprised of disc recordings, while CD 2 is drawn from the technically better medium of tape. That not only means that CD 2 is more listenable, it also means that programming logistics appear to have sometimes prevented incorporation of the best performances of particular songs. For instance, the recording of The Bonny Blue-Eyed Lassie which is used here was made by Diane Hamilton in the last months of Mrs Cronin’s life. The performance is nothing like as regal as that on BBC 19021, which was cut in 1952. Indeed, listening to Mrs Cronin struggling against the words and melody of one of the most translucently beautiful songs in the entire English language was an experience I found positively distressing. Also puzzling is the producer’s choice of Cuckanandy. The recording featured here was made by Séamus Ennis on 7th August 1947. It is decidedly inferior to Alan Lomax’s 1951 recording, and shows Mrs Cronin experiencing such chronic breathing difficulties, that at times she loses both the pitch and the rhythm. There are no less than four disc recordings of this piece in existence, plus the one by Lomax, plus one recorded by the Ritchies, plus two made by Diane Hamilton, which makes eight in all. One can probably scrub the Hamilton recordings, and it may be that the producers were reluctant to use Lomax’s in view of its availability elsewhere. That still leaves the Ritchie/Pickow. If the performance is no better than the 1947 recording, it will at least have the merit of better sound.[48]

As far as sound quality and performance vigour are concerned, the happiest compromise lies with the Ritchie/Pickow material. Fortunately theirs accounts for the largest segment of the recordings. I did detect one or two places where the original tapes seem to have been damaged. Otherwise, clear audibility combines with a spirited delivery, or as spirited a delivery as a septuagenarian can manage, and an interesting array of songs. Some of the most impressive English language songs Mrs Cronin knew were brought out during the Ritchies visit. I don’t know why, but I have a suspicion that Jean Ritchie achieved an empathy with Elizabeth Cronin, which went a lot deeper than the hospitality enjoyed by other collectors. Perhaps it’s that letter home, the one I mentioned earlier. Perhaps it’s the fact that they were both women, and both superlative singers. Perhaps it’s the fact that Jean Ritchie’s social background, albeit American and Kentucky, more nearly approached Mrs Cronin’s than did the backgrounds of any of the other collectors who recorded her. Whether there is any justification for such a suspicion, the Ritchies rationale for carrying out fieldwork - namely tracing the transatlantic origins of American folksongs - is nowadays regarded as fairly passé. Nevertheless, of all the people who collected from Mrs Cronin, they were the only ones who got her to sing The Derby Ram; that favourite of upstanding Americans from George Washington to The Dallas String Band.

When mapping out this article, I wondered whether I should offer a counterbalance to some of those comments about Mrs Cronin’s age and frailty. It should not be necessary. Anyone who has heard Sam Larner singing The Lofty Tall Ship, or Phil Tanner singing Henry Martin[49] will know exactly what to expect. They will know that it is not the ostentatious virtuoso in the prime of life, who raises the hairs on the back of the neck. It is the master performer of any age, who convinces their audience by being able to inject their own life’s experience into the song. In her younger days Elizabeth Cronin must have been a wonder to behold, and elements of a highly formidable style are still very much in evidence. But it is her ability to use these devices - the flowing rhythm, the shimmering ornamentation, the sudden and unexpected pauses - to work upon the unfolding of the story, and to hold the listener’s attention. Skills like these are to Mrs Cronin what shifts of vocal intonation and pace are to a good storyteller. Note the occasional slides, the places where the voice hovers, as though uncertain in which direction to go next. Feeble of voice, or short of breath, Mrs Cronin remained a virtuoso to the end of her days, and she remained the most compelling and emotionally satisfying of singers.

Earlier, I mentioned the question of value-freedom as it applies, or ought to apply, to collectors of folk music. That is because it is the collector’s role to observe what is there, rather than to interpose their own values over what is worthy of collection. With critics, however, the situation is rather different. They need to be aware of their personal and artistic values, and to use them in order to arrive at an assessment of the product under review. Simultaneously, they need to retain a measure of detachment. That is in order to be fair to all concerned, and so that they can convey to readers an idea of what the product is about, and whether it is worth buying. Among the more frivolous elements of the folk music press, this package will be reviewed virtually on the nod - after the reviewer has looked up how to spell the word scholarly, of course. Others will excuse the mistakes, and the methodological shortcomings, on the grounds that Dáibhí Ó Cróinín got a bit out of his depth and that, without his exertions, the songs of Elizabeth Cronin would still be lying on the archive shelf. Musical Traditions reviewers are made of sterner stuff than that and the bottom line is that, no matter how valuable the material, the mistakes in this book are too numerous and too basic to be acceptable.

But the mistakes are only the minor part of the disappointment. This book has left me with an awful feeling of wasted opportunity. With his expertise as a historian, and his family and communal connections, Dáibhí Ó Cróinín could have produced a first rate study of Elizabeth Cronin and the singing tradition she represented. It could have been a classic. It could have been another Tailor and Ansty.[50]

As things stand, I know very little more about Mrs Cronin’s life and society now than I did before. I know absolutely nothing more about her approach to singing. I do not know if the textual variance I found between her two recordings of Lord Gregory could be replicated with other elements of her repertoire. I do not know because no attempt has been made to compare different performances of the same song. Equally, no effort has been made to analyse her use of melodic variation between different recordings, or between different songs of hers which bear the same tune. Saddest of all, no attempt has been made to explore her lavish and almost legendary use of ornamentation. Before anyone wonders how I expect the publishers to accommodate all this extra detail, let me point out that the typeface is very large, as are the music notations, and for all they tell us, those titles-only songs from Bess’s list could have been reduced to a single page. With a little planning, and within the size limits of the present volume, Four Courts Press could have produced a book to satisfy the most meticulous of scholars, and the most enquiring of readers. Where on earth is the sense of including musical notations for the fifty nine songs which are already on the discs, when their stated sole purpose is to assist people in learning the songs? As Sandra Joyce’s note on these notations points out, the best way of doing that is by listening to Mrs Cronin. I heartily agree. There is absolutely no substitute. For anyone wanting to learn how they can make these songs breathe and live, the only way of finding out is by discovering how Mrs Cronin made them breathe and live. For anyone wanting to learn how to use their experience of life in the interpretation of these songs, the best way of doing so would have been to discover how they formed part of Mrs Cronin’s life experience.

Yet I cannot dispute that the book is unmissable. It is unmissable because it comes with a wonderful set of recordings of a wonderful singer. Do not misunderstand me. The person has not yet been born who cannot make a mistake, and I normally try to be as tolerant of other people’s clangers as I would like them to be of mine. Equally, I like to remember that different people have different methodologies. But this was the book the world was waiting for. It is not a cheap attempt to cash in on the current popularity of Irish music. It should not be judged by the standards of populist writing. It is not one of those awful pocket books, adorned with bodhrán decorations, which spouts vaporous nonsense about the 'heartbeat of Celtic music'. It is supposed to be a definitive work about one of the most important Irish singers ever recorded. Its publishers have proclaimed it as the publication of the year, yet it does not achieve acceptable standards.[51] Nor does it particularly add to our understanding of its subject. I know what the title says, but just turn the book over and read the blurb on the back. Not the paragraph which confuses the year of Diane Hamilton’s visit, mixes up Alan Lomax’s employers and the terms of reference of his Irish visit, and sets ‘child’ ballads in lower case, but the one underneath, which talks of offering "a comprehensive account of an extraordinary singer and her distinctive singing style".