Hidden Fermanagh:

Traditional Music and Song from County Fermanagh

Book: Cyril Maguire (with transcriptions by Sharon Creasey)

Fermanagh

Traditional Music Society; paperback; 180 pages; 2003

CD: Fermanagh

Traditional Music Society – no catalogue number; 48 minutes; 2003

Click here to head straight for a review of the CD

There’s a boat just now

launched at Knockninny, whose equal has never been seen;

And nobody’s christened her

yet, but I call her the Long Ferry Queen.

Indeed she’s a beautiful

picture, all youse that are up for the fun.

Just take a short trip to

Knockninny, and sail down to ‘Skea with Pat Gunn.

(from Pat Gunn’s Boat)

It is easy to get lost in Fermanagh, especially around the

shores of Upper Lough Erne where a maze of highways and (more often) byways

appears determined to draw you inevitably to the waterside and signposts always

seem to read “Newtownbutler 7”. Finding traditional music in the county can

often be an arduous task too. Its largest town, Enniskillen, has long been

Country and Irish territory and, although there are notable exceptions, finding

a session can prove difficult.

That is not to say, of course, that the county lacks a musical heritage, just that (as the title of this welcome publication and its accompanying CD suggest) it lacks the profile of Clare, Galway or neighbouring Donegal. Its best-known musical product has undoubtedly been Cathal McConnell whose work with The Boys of the Lough has taken his local repertoire onto a global stage and the county has also given us musicians of the calibre of Seán McAloon, Séamus Quinn, Tommy Gunn, Larry Nugent and Jim McGrath, as well as singers such as Rosie Stewart and Gabriel McArdle.

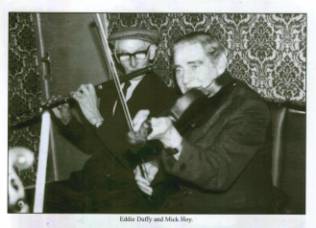

Yet, apart from McConnell’s efforts, it was probably the visits of the Belfast boys, such as Desi Wilkinson and Gary Hastings (as Ciaran Carson recounts in Last Night’s Fun), and the cross-border collaborations with the likes of the Leitrim fiddler Ben Lennon which have had a lasting impact. The young Desi and Gary spent their weekends lapping up the knowledge of Mick Hoy, the singer, fiddler and storyteller from Cosbystown who himself had acquired much of his repertoire from the flute-player Eddie Duffy. Cathal, of course, knew both Eddie and Mick, and recounts his first meeting with the latter as follows:

“I

met Eddie first in ’71 or’72. I think he was seventy-eight years old at the

time. It was at some musical function. I can’t remember where, and at some

point he says to me, “I have tunes that nobody knows. I’d like you to have

them,” which was an honour. So we drove down one cold winter’s night. We almost

didn’t make it because our first driver let us down, but it was lucky that we

did because Eddie was waiting in his good suit. And there was a Swedish guy

called Karl Jonson – he called himself, in Irish, Cathal McShane – he was there

with his big tape recorder, and of course my sister Maura was there as well. I

think he was going to give some of that stuff to the archive, to Breandán

Breathnach. I think he was going to do that. Whether he did or not, I don’t

know.

“I was excited because it was a great find of tunes, rare tunes, strange tunes, from this area – nothing I had ever heard before in my life. I think the first tune he played was ‘O’Connell’s Reel’. He played a lot of stuff that he never played afterwards – ‘The Hawk of Ballyshannon’, ‘Paudeen O’Rafferty’, ‘The Girl in Danger’. He played two versions of ‘The Pinch of Snuff’ – nearly the same – and ‘Lannigan’s Ball’. It was a treasure of tunes and he started playing first. And then later on Mick came in and we played some tunes together. We made a very special tape. I set about deciphering these tunes and started playing them, but I never thought they would be popular. It was a wonderful experience and thankfully Eddie was alive for a long time after.” (Hidden Fermanagh, p.34)

Indeed, Eddie lived until 1986, the year in which the Arts Council of Northern Ireland published Here is a Health, a cassette release of songs, fiddle tunes and stories recorded by Seán Corcoran in the Derrygonnelly area between 1979 and 1985. Sadly, Eddie does not appear on that recording, although Mick Hoy is the undisputed star of the show, featuring on no less than ten of the album’s twenty-six tracks and providing irrefutable evidence of his musical genius and sheer good-time humour.

One

of the singers on Here is a Health was Annie McKenzie, originally from

Derrylin and described in Seán’s notes as “Landlady of the Linnet Bar in Boho,

a focal point for local singers and musicians” and turn to page 60 of Hidden

Fermanagh and you will discover a photograph of Annie with her daughter,

Eileen McGourty, standing outside that same pub seventeen years on (and,

according to a sign on the wall, the McKenzies still run the bar).

One

of the singers on Here is a Health was Annie McKenzie, originally from

Derrylin and described in Seán’s notes as “Landlady of the Linnet Bar in Boho,

a focal point for local singers and musicians” and turn to page 60 of Hidden

Fermanagh and you will discover a photograph of Annie with her daughter,

Eileen McGourty, standing outside that same pub seventeen years on (and,

according to a sign on the wall, the McKenzies still run the bar).

The connections described above and the earlier quote from Cathal McConnell are vital to an understanding of the genesis of Hidden Fermanagh since, according to Cyril Maguire’s introduction:

“The idea for

this project came originally from Cathal McConnell. He mentioned to me, in late

2001, that he would like to put together a CD of Fermanagh music, that had

never before been recorded. I knew it would be possible to do this, as, down

the years, Cathal had put together a large number of Fermanagh tunes on tape

for me, mostly those of Eddie Duffy and Mick Hoy. He was also anxious to

include the material of John McManus, as John had always been his main source

in the home part of the county. From the start, therefore, the project came to

focus on two parts of the county, Derrylin and Derrygonnelly, and their

surrounding areas.” (p.1)

Both Cathal and Cyril also knew that John and Valerie McManus were connected to a very important document, The Gunn Book, which was itself to become integral to their project. The Gunn Book is a collection of one hundred and seventy-eight dance tunes compiled by the fiddler John Gunn (an ancestor of John McManus) during the middle part of the nineteenth century, though it is reckoned that a few tunes may have been added by another hand. Although it does contain several well-known tunes, the manuscript’s importance lies in the sheer number of rarities it contains, some of which are played on the CD, and the document is rightly seen as an important part of the local heritage. As Cyril Maguire recounts:

“The manuscript is not regarded as the property of any single individual but as part of a wider family legacy. Some years ago it was passed into the hands of John Reihill whose aunt was married to a grandson of John Gunn’s. John Reihill and his wife live on Inishcorkin Island on Upper Lough Erne, not far from Derrylin. They are the only people who continue to live, and to make a living, on one of Lough Erne’s islands. They farm and, during the summer months, run a restaurant for passing cruisers. John describes himself as the ‘custodian of the book’.” (p. 24).

According to John McManus, John Gunn was not only something of a dandy, but also learned much of his music from a travelling fiddler called Celter who might have come from Donegal. As John McManus comments:

“There’s an awful Donegal tendency in them tunes, and when you listen to Johnny Doherty and them playing, it’s even the same bowing, very flamboyant bowing, you know, from toe to tip. You see the fellas up in Clare now, and it’s only the tip, they do it all with the fingers.... but the Northern style, it’s with the bow. The triplets are done with the bow.” (p. 26)

I shall return to those tunes shortly, but let us now

consider the first half of Hidden Fermanagh which consists of some  seventy

pages and is divided into four chapters, each featuring several archive or

recently taken monochrome photographs. Some of these are real gems, such as the

pairing of the Harp of Erin Céilidhe Band, all neatly coiffed and suited and

featuring a bevy of McManuses as well as their relation Tommy Gunn (who for

some reason was also known as Jason) and the more bohemian Starlight Dance Band

(in which John McManus swapped his fiddle for a saxophone and which also

appears to feature the oldest drummer in musical history). There’s also a

superb picture of Red Pat Gunn, John’s grandfather (of ferry boat song renown)

and a stark portrait of Felix McGarvey, a flute player, and his unnamed wife

standing to attention in poses indicative of unfamiliarity with photography.

This dates from c. 1956 but, from their garb, it could have been taken at any

time in the previous fifty years. Readers will also find a portrait of a very

hairy Cathal McConnell and a sublimely stunning full-page photograph of Mick

Hoy.

seventy

pages and is divided into four chapters, each featuring several archive or

recently taken monochrome photographs. Some of these are real gems, such as the

pairing of the Harp of Erin Céilidhe Band, all neatly coiffed and suited and

featuring a bevy of McManuses as well as their relation Tommy Gunn (who for

some reason was also known as Jason) and the more bohemian Starlight Dance Band

(in which John McManus swapped his fiddle for a saxophone and which also

appears to feature the oldest drummer in musical history). There’s also a

superb picture of Red Pat Gunn, John’s grandfather (of ferry boat song renown)

and a stark portrait of Felix McGarvey, a flute player, and his unnamed wife

standing to attention in poses indicative of unfamiliarity with photography.

This dates from c. 1956 but, from their garb, it could have been taken at any

time in the previous fifty years. Readers will also find a portrait of a very

hairy Cathal McConnell and a sublimely stunning full-page photograph of Mick

Hoy.

The book’s opening chapter, A Life in Music, is based largely upon an interview with John McManus, Valerie providing appropriate interjections, and traces his musical story, being particularly fascinating in considering his ability to play different types of music depending upon the band he was in at the time and the musical company. Despite its relative isolation, this part of Fermanagh seems not to have been off the beaten track as far as visiting musicians were concerned, though John also met others at his bands’ gigs around the Northwest of Ireland.

“Valerie: Who was

that piper, the one with the long fingers who said that he heard the fairies

were teaching in Fermanagh when he heard Tommy Rourke?

“John: That was Johnny Doran and he was coming through Lisnaskea this day, and he heard of Tommy Rourke playing, so he made it his business to go to Tommy Rourke’s and he says when he’s leaving, ‘The fairies have been in touch with that man.’ That’s what he told other people when he left... he didn’t tell Tommy that, now.” (p. 17).

The impact of John’s story lies in the strength of its telling and his ability to encapsulate events in just a few words, but also leave much to the capacity of the reader’s imagination. When asked by Valerie how long Uncle Hugh’s wedding lasted he simply replies, “Uncle Hugh’s wedding went on for seven weeks”. That being said, Cyril Maguire is obviously a very capable interviewer.

The chapter ends with a reference to the conversation leading onto a discussion about local songs, at which point Valerie and John commence singing Pat Gunn’s Boat, a recording of which can be heard on the CD.

While the second chapter recounts the story of The Gunn

Book, the third, A Life on Stage, is entirely devoted to an interview

with Cathal McConnell. Usefully, this also includes a detailed list of every

single Fermanagh-related song or tune recorded by Cathal, referring also to the

source of each piece. Cathal recounts his own musical genesis and remains

particularly sanguine about his failure to win a talent competition in Bundoran

(“Why were you eliminated? “Because I wasn’t from Donegal” , p. 41).

The final chapter, Song and Verse, focuses upon the Fermanagh song tradition and is, in many ways, the least coherent section of the book. Indeed, since Maguire fails to set out his stall at the chapter’s onset, his modus operandi is not immediately apparent. As Cyril refers to some, but not all of the songs sung on the CD, it reads in part like extended sleeve notes (indeed, as in the references to Cathal McConnell’s singing of Erin the Green and Gabriel McArdle’s Bessie, The Beauty of Rossinure Hill, on page 66, it appears that the author is referring to songs which feature on a subsequent CD release). At other times, however, it seems more like an essay on local songwriters and the subjects of their songs.

He begins by recollecting the songs composed by the poet Peter Magennis (1818-1910) from Knockmore, near Derrygonnelly, an acquaintance of Carleton, Allingham and Lady Wilde. Magennis was a powerful writer whose disappearance from Irish literary history is thoroughly undeserved. However, this account drifts into a discussion about the manufacture of poitín which then wanders onto the subject of Pat Gunn’s Boat before suddenly leaping to the songs composed by Cathal McConnell’s father, Sandy. This then takes us onto the subjects of domineering mothers and then to a popular recitation in the Derrylin area called Maxwell’s Ball.

Now all of this is very informative, but it would have been far more purposive for the reader to have been provided with more general details regarding the local song tradition at the beginning of the chapter, such as: the particulars regarding previous collections of material from the two areas; the types of songs collected; and, the current popularity of traditional singing in Fermanagh. Instead snippets of information appear almost randomly. So, when Cyril moves on to a discussion of songs popular elsewhere and in other traditions we finally receive a reference to Seán Corcoran’s Here is a Health and later (on page 63) discover that Harry Bradshaw collected songs around the Boho area in 1981.

The reference to Seán Corcoran’s collection appears in a discussion of a song he collected from Annie McKenzie, The Frog’s Wedding, where, unfortunately, while admitting the possibility of “allegorical interpretations”, Cyril gives credence to the view that “it is simply a children’s song made up and sung for enjoyment” (p. 61) espoused by John Moulden (sadly, misspelt here as “Molden”).

Now, forgive me if I’m wrong, but songs deliberately aimed at children do not usually include verses such as this, which seems not to require any allegorical interpretation whatsoever:

“Arragh, Missie Mouse, will you wed?”

Fol-lie, linkum-laddy,

“Will you come into me bed?”

Tidey-ann, tidey ann, diderum-diedum-dandy.

Anyone with any knowledge of ranarian sexual behaviour knows full well that male frogs are incessantly promiscuous and, as a result of their myopia, are not always accurate in terms of the direction of their Priapic intentions. Indeed, this means that when froggie feels the urge to merge, he’ll jump on anything that bears the slightest resemblance to the generative obligations of his species (including many a poor mouse!). And what are we to make of the line “Frog rode up to Mouse’s hole”?

However, rather than giving attention to the song which Annie McKenzie actually sings on the CD, the rare Kate from Ballinamore (previously recorded by Geordie Hanna on the Topic album On the Shores of Lough Neagh – 12TS 372), we are now suddenly whisked away to the subjects of the hiring fair and the singing of Willie McElroy from Carrickapolin, near Roslea, though, according to Cyril, he is generally associated with the Brookeborough area (which is some distance from both Derrygonnelly and Derrylin). The relevance of this discussion is fundamentally questionable since none of the songs on the CD nor any of those subsequently transcribed in the book actually mentions a hiring fair.

Next, and rather suddenly, the reader is sped back to a discussion of Peter Magennis’s work and the case of one Dominick Noone “who joined the Ribbonmen in the early years of the 19th century, informed on them and for this was assassinated and thrown down a very deep pothole in the Boho Mountains” (p. 63). This moves on to the song collected by Harry Bradshaw from one Miles Doogan of Meeniclybawn, a townland close to Garrison. Forgive me, but having travelled the road many times, Garrison is some distance from Derrygonnelly.

The last two sections of the chapter relate to songs sung by Gabriel McArdle and Catherine McLaughlin, yet, as previously mentioned, the McArdle song Bessie, The Beauty of Rossinure Hill does not actually appear on the CD (where he sings I Have Travelled This Country) although the reader is informed that “It is a big song, over six minutes long, and Gabriel... sings it unaccompanied”. (p. 68)

The concluding discussion of Edward on Lough Erne’s Shore (sung by Catherine McLaughlin on the CD) is by far the weakest in the entire chapter. For starters it includes one of the most redundant footnotes in Irish publishing history (and, believe me, there’ve been many). We are informed that the song was recorded by Rita Gallagher on her album Easter Snow and the linked footnote simply repeats this information without providing any details regarding the label or year of recording.

However, Cyril is wide of the mark in asserting that this “is another song of transportation”. That last word is not mentioned in the song – indeed young Edward is referred to as “banished” and the only reference to the terms of his banishment is contained in the last verse:

Seven long years would soon pass over,

And we’d live happy on Lough Erne’s shore.

Since no information is provided about the origins and possible date of the song it is impossible to draw this conclusion as the reasons for banishment could vary considerably. Cyril does observe that “almost identical verses appear in Poems of Peter Magennis under the title of Song. Air – “Youghal Harbour”, though suggests that it cannot be certain whether the poet (who died in 1910) actually wrote the song or collected the lyrics from somebody else. Conversely, Dermot McLaughlin’s sleeve notes for the Dog Big Dog Little album (Claddagh CC51CD) boldly assert that the song, performed there by Gabriel McArdle, was definitely the work of Magennis. Since the song utilizes some typically Victorian florid imagery, it is quite possible that McLaughlin is correct. (By the way, the transcription of the song on p.140 includes an astonishing error – the line “Why did you leave me, my love, a stór?” being rendered as the thoroughly nonsensical “Why did you leave me, my love astore;”!)

The second section of the book is entirely devoted to transcriptions (undertaken by Sharon Creasey) of dance music and songs – over one hundred tunes and some thirty songs. Here Hidden Fermanagh decidedly steps up a gear. Firstly, the presentation of the material is utterly admirable, indicating that the authors (I’m including Sharon here) have clearly considered the best way to display the tunes. No more than two ever appear on one page (unlike say Allan’s Irish Fiddler where as many as four can be found on a single sheet) and each tune has clearly been thoroughly researched with notes revealing actual or possible sources, similarities with other tunes and alternative titles available. Obviously, sometimes little can be said other than that the tune comes from the repertoire of a particular musician, but, wherever possible, the authors have distinctly added to our musical knowledge. However, sometimes the research might have been conducted more diligently – The Boy in the Gap, for instance, was composed by Paddy Taylor, the Limerick-born flute-player, but this information has not been included.

The Milltown Lasses, a rare tune, was recorded by Rose Murphy on Milltown Lass (Ossian OSS-21) but this is not mentioned.

Sometimes too, as in reference to The Boys of 25, the note suggests that the tune is on the “accompanying CD” when clearly it is not, but on page 100 all is finally revealed when The Humours of Swanlinbar is described as being “played on CD, vol. 2, by Brenda McCann”. Well, one might hope so, but the very next page reveals that one Catherine Dunne plays Hand Me Down the Tacklings on CD volume one. Neither Catherine nor the tune appears on said album

Of course, tunes from The Gunn Book take their rightful pride of place and some of these are most unusual. Take, for instance O Squeeze Your Thighs, itself an oddly-titled jig, which the authors have identified as a six-part version of The Munster Buttermilk, adding:

“Breandán Breathnach

collected a similar version from Johnny Cathcart of Derrylin in 1966 and

included it in Ceol Rince 2. According

to John McManus, Breathnach didn’t actually see The Gunn Book. They met in John’s house and Johnny Cathcart was

there. In order to encourage Johnny to play, John said to him, ‘I suppose you

don’t remember that tune,’ whereupon Johnny promptly played the above.” (p. 77)

Sometimes too, the local tune titles are equally revealing. The

Maho Snaps, for instance, was named after “a

particularly bumpy stretch of road alongside Lough Erne, between Enniskillen

and Belleek” (p. 81), or that The Grand Spy

is a local corruption of Grant’s Strathspey

(a tune which has become even more widely known and even more corrupted as The

Graf Spee!).

The thirty songs include several composed by Sandy McConnell who clearly

regards some of the inhabitants of other Fermanagh villages with a jaundiced

eye, but certainly himself possesses a sharpened wit. Take this, for example,

from The Second-Hand Trousers I Bought in Belcoo:

When the wife saw

the trousers, she flew in a rage,

Sayin’, “They’re no

wear at all, for a man of your age;

With one leg so

black and the other so blue,

Ah they’d rob a

child’s bottle up there in Belcoo.”

The Knockninny Men fair little better:

‘Sure their footballers do badly, they lose all their matches.

They’re awful bad kicks and they’re even worse catches.

And the Balenaleck boys can run through them in batches,

What’s gone wrong, what’s gone wrong, with the Knockninny men?

(Anyone acquainted with the local area might be puzzled by the reference to “Balenaleck” which, presumably, is a misprint of Bellanaleck or has been deliberately spelt in this way to reflect Sandy’s enunciation.)

Like these two songs, several of those transcribed here are clearly of local origin. These include: Bessie, the Beauty of Rossinure Hill (the hill in question is between Knockmore and Boho Mountain); Dominick Noone the Traitor; Edward on Lough Erne’s Shore; The Groves of Boho (pronounced “bo”, by the way, if you’re wondering about peculiar rhymes); The Maid of the Colehill (an area now a housing estate in Enniskillen); My Charming Edward Boyle (the story of an emigrant from Roslea); The Roslea Farewell; Sergeant Neill (a local potato sprayer); and The Town of Swanlinbar (just over the border in County Cavan). The remainder are drawn from all manner of sources: Sweet William’s Ghost is a Child ballad; The Banks of Kilrea comes from County Derry; The Bonny Green Tree appears in various collections, including The Songs of Uladh and More Irish Street Ballads; then there’s The Banks of the Clyde and Dumb, Dumb, Dumb which I am pretty sure comes from England.

Overall, it is an intriguing snapshot of the local repertoire which by no means claims to be all-inclusive, but suggests a broad range of subject matter. Oddly, in comparison to the recordings made by Keith Summers (see The Hardy Sons of Dan) there are no hunting songs and only one reference to Gaelic football (The Knockninny Men). Equally, as with both Keith’s recordings and Here is a Health no recent political songs have been included.

In contrast to the book, the CD is somewhat

disappointing (and, to make matters clear, I am referring here to the only Hidden

Fermanagh CD released to date – volume one). It is only just under forty-eight

minutes long. Now, of course, this would be regarded as more than satisfactory

in those halcyon days of vinyl, but our expectations have been heightened by

other similar projects which have explored the greater potential of the CD

format. The products of Sligo’s Coleman Heritage Centre, for instance,

generally last for at least an hour as does The Fiddle Music of Donegal

series.

The second and perhaps more substantial regret lies in the fact that the entire album consists of new recordings, so anyone expecting to hear Eddie Duffy, Mick Hoy or the RTÉ recording which Harry Bradshaw made of Miles Doogan singing Dominick Noone the Traitor might feel slightly short-changed.

Thirdly, the CD’s liner, a mere four pages in length only provides the track listings, personnel and tune sources, making acquisition of the book essential for those who wish to learn a little more (to be fair, the CD by itself is remarkably cheap in comparison to most commercial releases).

The vast majority of the tunes and songs which appear on the

album have not been released elsewhere. The exceptions are Milltown Lasses

and Kate from Ballinamore (respectively recorded by Rose Murphy and

Geordie Hanna, as mentioned previously), while The Opera Reel has,

according to the book (p. 102) been recorded by De Dannan (though not on any of

the band’s albums possessed by this reviewer, so clarification would be

welcome). Additionally, Edward on Lough Erne Shore appears on the Dog

Big and Dog Little album, sung by Gabriel McArdle, albeit under the title Edward

of Lough Erne Shore. It should also

be noted that the second tune of the opening set of reels, The Primrose Lass,

is not the same as The Primrose Girl transcribed in the book, and is, I

believe, the same tune as recorded by Matt Molloy, Paul McGrattan and Felix

Doran.

The subject of tunes raises another vital issue. If the overall project’s purpose is to draw attention to local tunes which have not been previously recorded, then why have the producers (Messrs. McConnell and Maguire) chosen to employ so many backing musicians and, on at least two tracks, sometimes highly inappropriate accompaniment? The opening track (Dickie Gossip/The Primrose Lass/Uncle Hugh’s – a set of reels) is an ensemble piece featuring no fewer than two fiddles, three flutes and an accordion, so really does not need an additional couple of guitars and a bouzouki player to bolster the sound. Indeed they only serve to swamp the melody. This is utterly apparent on the reels Milltown Lasses and Lady Gardener’s Troop where Brenda McCann’s fiddle is thoroughly dominated by Pat McManus’s guitar. Equally, the following track where McCann is joined by Cathal McConnell on flute sounds nothing less than Frankie Kennedy-period Altan, thanks to the presence of both a guitar and bouzouki. This process reaches its nadir on Lady Lübeck/Ereshire Lasses (an old spelling for “Ayrshire”) where there are more accompanists than the actual melody instruments, two fiddles.

Thankfully, Top of the Hill is played initially as a solo piece by whistler Francis Rasdale before he is joined for a couple more run-throughs by Cathal McConnell, but the magic and grace of their playing is immediately undermined when a swathe of fiddlers and accompanists appear for the set’s second tune, Katie’s Lilt.

The songs are very much a mixed bag. Gabriel McArdle is on typically eloquent form on the unaccompanied I Have Travelled This Morning, but Catherine McLaughlin’s perky rendition of Edward on Lough Erne’s Shore is utterly ruined by some electronic keyboard backing which even Clannad might have considered inapt. Valerie and John McManus’s Pat Gunn’s Boat should have been unaccompanied, but instead gets the guitar and bouzouki treatment. Fortunately, the magic of Annie McKenzie’s Kate from Ballinamore is left unsullied.

However, despite all of these qualifications, it should not be taken that the album is not worth acquiring – the tunes are too rare, the melody instrumentalists are on top form and the singers more than merely impressive. It even has to be said that the accompanists are no session hangers-on, but just far too prominent in the mix.

There are three further reasons for obtaining the album. The first is the duet by Cathal and Mickey McConnell on their father’s song Ballyconnell Fair which has to be regarded as one of the most uproariously hilarious recordings ever made (and it was recorded before an appreciative audience somewhere, although the liner notes state that all the tracks were laid down in a studio at Monea). The reason for the hilarity is simple. While Cathal clearly recalls all the words of the song, Mickey clearly does not and compensates for his memory lapse by joining in the chorus with increasing fervour (even ending his contribution with “Yee-hah”!). The other is the succeeding track, The Opera Reel, lilted by Valerie and John McManus with Cathal and joined by Sharon Creasey on flute (although it has to be said that Richard Creasey’s bouzouki is entirely unnecessary here). Finally, the closing set of waltzes, featuring the fiddle of Pat McManus, accordionist Jim McGrath, plus Cathal and Cyril on flutes, is utterly entrancing and deserving of a wide audience.

Overall, Hidden Fermanagh is a project thoroughly deserving of your attention and acquiring a copy of the book is essential. Further information can be found at www.fermanaghmusic.com/.

Reviewed by Geoff Wallis for Musical Traditions

magazine – www.mustrad.org.uk/.